Amelia Winata: Many commentators have written about your work in regard to functionality. For example, in an Artforum preview of your 2020 show Kit-set In-transit at Fine Arts, Sydney, Toni Ross wrote about your works as "household goods in the IKEA mold" and "things less redolent of the domestic sphere, such as transport grab handles and stop buttons." So really she describes them as domestic items. But then she suggests in the same piece that your sculptures have a superfluous quality, saying that they "sparsely populate the steel sculptures as though sprouting from their metastatic impetus.” There is a kind tension identified by Ross, a tension to do with functionality.

Yona Lee: I think that's an interesting observation. I didn't really think about the functionality of my work until an exhibition I did in Seoul back in 2016 [In Transit, Alternative Space LOOP]. At that time, I had limited support, so I was installing with just one welder, and we had five days to complete the install. I was forced to sleep in the gallery in a bed that I installed as part of the exhibition to meet the deadline.

AW: Was the bed already part of that install?

YL: That install, yes. But it wasn't intended to be slept on.

AW: What was your intention with the bed initially?

YL: At the time, I was focused on thinking about different spaces and time, about the impact of the development of technology, transportation, and the internet. It's all about the compression of time and space. I started thinking more about these concepts in the beginning and wasn’t aware of the functionality of the objects that I was using. So, in the Seoul project, I was using some of the objects as props and aspects of functionality were arbitrary at that time. For example, there was a shower just hung up, but not working. But the lamp was working in the space. I had a bed, but I had a stainless [steel] bar across the bed so that people couldn’t sleep on it. The exhibition was in an underground concrete industrial space, with no windows. And it was winter. Even though it was a harsh environment, it was cozy to sleep within the structure. It was a revealing experience as I started thinking, “Actually, I can make a livable structure." That's when the functional part of the work came to me. And then sometimes I reverse or revert the functionality of the object. Like in this exhibition at Gertrude, having bus handles really high so that they're hard to reach.

AW: Maybe then it's worth describing what this exhibition at Gertrude is composed of. So, it's three small sculptures…

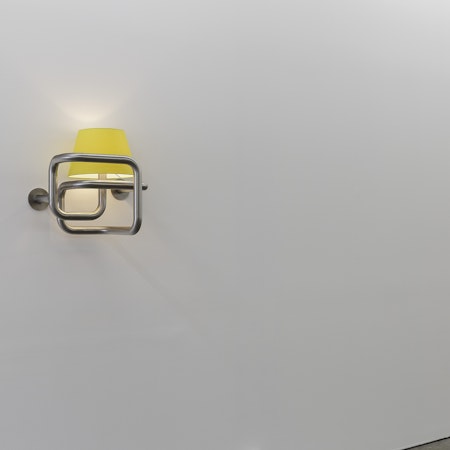

YL: Yes. There's a clock with a bench, and a lamp and bus handles.

AW: Hung up high on the ceiling.

YL: Hung up really high so that it’s out of reach. It becomes dysfunctional. I play with the fact that these objects are so familiar to us. We can't imagine having no chair in a room or no lamp or light in our built environment. And sometimes if you play around with an object a little bit, it can create a strong reaction—say, if a light is out. it's interesting that Toni Ross pointed out the IKEA element, because that is true. I think that link is probably to do with how things are made. IKEA is made so that it's easily transportable. There's a temporariness to the object, so you can always pack it down and then move.

AW: The way I see it is that you have kind of disrupted the functionality of familiar objects, and that almost makes these more visible in the space.

YL: Bringing different functionalities into the space also creates a tension. I like my objects to have some functionality so that people can actually use the work. It's invitational, but without being like, "These are interactive installations. Please come." It's more a subtle invitation that plays with familiarity. But also subverting the intended function of the object makes you look at them in different ways.

AW: But you're also using the objects to draw attention to the space of the gallery—the gallery’s architecture. We spoke earlier about your work not only subverting the function of the kind of objects they perhaps represent, but also subverting the framing mechanisms of art. From a traditional standpoint, there's a predetermined language that different mediums have in the gallery. What's that subversion that you're performing with your sculptures, with your particular hanging style, for example?

YL: When we think about different mediums, often paintings are placed on the wall and then sculptures on the floor, and their definition is determined by architecture. Having my work adapted to different formats is a way to extend one's perspective of what a sculpture is. When you think about music, different instruments have different pitch ranges for example—often people refer to a violin as having a female voice, or a cello as having a male voice. And I see the same thing with space. A room needs a ceiling, walls, and a floor. They offer different pitch ranges, in a way.

AW: For the most part, you physically visit a site and then form your exhibition around that. And you did formulate this exhibition around the Gertrude gallery, but you actually hadn't visited it prior. Was that a challenging process?

YL: I usually try to visit the site before the exhibition, more than once if I can. But sometimes, practically, it’s not possible to do that. For Gertrude, I knew that I was making some discrete objects for the exhibition. So I was thinking a ceiling as a whole, wall as a whole, floor as a whole. So how the space was built didn't quite matter. It just needed to…

AW: Be a traditional gallery space?

YL: Yeah, because I'm talking about the format more than the details of the space.

AW: Yes, I think it's really interesting looking at how you think about exhibitions. You're so meticulous and you plan ahead and everything has meaning, right? For the most part, these sculptures seem so simple, but they have been so painstakingly formulated. One of the things that really struck me when we were installing was that you had two lampshade possibilities, yellow and a green, and each colour completely changed the mood of the exhibition. It might be interesting to think about the logic of choice in relationship to the perceived mass production that your works represent. And I say perceived because—we've discussed also—that really, your work is handmade. You make it yourself, for the most part. So there's this tension also between craftsmanship and mass production.

YL: The lampshade was a way to bring color into my work. When you think about stainless steel, it’s quite cold and very industrial—very impersonal. When we think about historical steel sculptures such as works by Anthory Caro and Richard Serra, they are usually associated with a prominent masculine undertone. The objects that I use soften the masculinity. The lampshade and the clock, they're quite emotional objects, in a way.

AW: There's something very endearing about them.

YL: There's the possibility for more stories to them. I carefully chose these objects so that they’re not loaded with meaning. For example, I wouldn't necessarily use a lampshade from my childhood or use bus handles from, I don't know…

AW: That are branded?

YL: Yeah. I try to choose objects that are as neutral as possible. I mean, nothing can be fully neutral. But I mean neutral so that when an audience comes in and looks at these objects, it's very open for them. Because everyone has different relationships to these objects. I think for me, it was kind of important for it to be just a clock or just a lamp or…

AW: But you did carefully choose between a green and yellow lampshade.

YL: I have a very limited choice of colours because I use colours that are commercially available. I think it's interesting to think about why these colour options are available. When you think about these colors, they are for a certain purpose. For example, when we think about the bus context, often these rails and handles are brightly colored. Bright colours are used to make objects easier to see so these colours are functional because they support recognition capabilities. Also, when it comes to colour choice, I think about balance. And in the end, I leaned more towards primary colours for this exhibition.

AW: Which is, again, kind of generic.

YL: Generic, yes. I like that word. Generic.

AW: Toni Ross referred to your work as “normcore,” which I thought was a little bit... I was like, "That's a little bit harsh." But you really liked that description.

YL: I like that description because it’s deliberately generic. This gives it power to be relatable to many people and appreciates the quality in ordinary things.

AW: Yeah. Because it means that there's a kind of standard logic.

YL: They’re available for everyone, no? These are not expensive objects.

AW: Yes, it's an interesting description. Though if we're thinking about mass production and standardisation as themes in your practice, it's probably quite interesting for audiences to know that you, as I mentioned earlier, you manufacture most of your work. You weld. And that is almost counter to the notion of factory production or producing things en masse. Yours are actually quite delicately produced objects. Can you speak about why it's so important for you to have your own hand in your work?

YL: I think it's probably more to do with the practicality of things. For bigger projects, I build a small team and I have a welder helping me. But with the smaller objects, I just haven't had a chance to train someone. The professional welders can be conservative in the way they operate, and my work does not follow that type of process. And I enjoy making. It's really interesting when you think about stainless steel, we think it's quite an industrial material, that it's very rigid. But when you apply heat, it reacts.

AW: It softens dramatically.

YL: Yeah, and it's quite unexpected how it reacts. I was talking to my bending supplier, and he said every day, depending on the weather, they have to change the setting for their machines because the steel reacts differently to the weather and the humidity. It’s like a living entity.

AW: I want to turn to the question of design now. The word design is used a lot to describe your work. You're designing your work and there's kind of references to design history through your use of stainless steel. In Melbourne at the moment, there's quite a big discussion about the crossover between design and visual arts, particularly off the back of Melbourne Now, for example, and often the discussion is kind of a little bit negative. But I wonder how you see your work in relationship to design. If you see some kind of trend going on in New Zealand, even.

YL: I don't think we have that crossover in New Zealand to the extent that it is here. Like with Melbourne Now or the Design Fair. I see that more here in Australia—even with dance. I see that there are a lot of dancers showing in the visual art context.

AW: That's interesting. With that in mind, what about design is your work reacting to? Does it want to be a hybrid of design and art? Does it want to react to the history of design?

YL: Hybridity acknowledges a form of categorisation which I want to blur with my work. I'm interested in how people define what's design, what's art and what's architecture. People often say what distinguishes fine arts from design or architecture is the absence of functionality. This conventional idea inspires me to play with functionality to challenge set boundaries.

AW: We talked about a spectrum earlier—how you like to flip things so that you're looking at both ends of a spectrum and then what the possibilities are between.

YL: And I think I'm more interested in connecting them. I think it's more about connection.

AW: So, connecting functionality and lack of function.

YL: Yes, connecting.

AW: Connecting aesthetics.

YL: Different spaces.

AW: Yeah, connecting spaces. Connecting the invisible and visible.

YL: But I think when you really strip back the essence of design, art, and architecture, they come from same space. And I think it's more about focusing on the essence of it, rather than the details around it—the details that make us distinguish between art and design and architecture.

AW: Yeah, absolutely. They dovetail with one another, the art, architecture, design. Let's end on a final question. Who are the artists who have influenced your practice?

YL: There are many artists who influenced me while I studied at Elam [School of Fine Arts] Auckland. In particular Peter Robinson and p. Mule. Peter influenced me about the precision of forms and spatial qualities. And p influenced me to be more intuitive and to think about who I am. I remember she knew I was into music at the time, so she encouraged me to embrace that, which I couldn't really do at the time. But over the years, I eventually did.

AW: It's funny because they're kind of also kind of opposite-

YL: Quite different. Yeah.

AW: Very precise and then very intuitive, which kind of coalesces in your work.

YL: Exactly, exactly.