30 March -

3 November 2020

Gertrude Contemporary

21-31 High Street, Preston SouthGertrude Glasshouse

44 Glasshouse Road, CollingwoodHope in the Dark

In response to a rapidly changing world - Gertrude presents Hope in the Dark, a street-facing exhibition in the windows at Gertrude Contemporary and the window vitrine at Gertrude Glasshouse. This project will evolve over the coming days and weeks (or as long as possible) while our regular programming is on hold.

Exploring ideas of confusion, resignation and anxiety offset with humour, hope and resilience, these gestures offer an opportunity for a bit of aesthetic and comic relief while we collectively #stayhome.

Follow this evolving exhibition on our social media channels:

Instagram @gertrudecontemporary

Facebook @gertrudecontemporary

Twitter @gertrudecontemporary

Notes on the artworks

While our interior gallery spaces remain closed to our community, Gertrude presents the outward looking and internally ruminated exhibition Hope in the Dark in our foyer spaces at Gertrude Contemporary and in the window vitrine of our project space Gertrude Glasshouse. Hope in the Dark recontextualises recent works by artists close to Gertrude to reflect upon the uncertainty, anxiety and vulnerability of this calamitous era as it begins to unfold, or indeed, unravel. Intended to evolve throughout the duration of the extraordinary phenomenon of a global shutdown, the works in Hope in the Dark signify the confused sentiments we now all collectively share, yet apart from one another. Infused with gallows humour, the works attempt to offer a degree of reassurance that we are all in this situation together, that our confusion is shared, and yet we must, for our own sanity and emotional fortitude, remain optimistic that this will at some point come to pass.

Intended to accumulate over time, and change as the situation shifts, Hope in the Dark began with a work from an exhibition foreshortened, Weevils in the Flour by Lewis Fidock and Joshua Petherick. The suspended sculptural work Tongue, 2019 now takes on an altogether different resonance in light of the bizarre global paradigm we now find ourselves a part of. A found slide, with a patina that indicates a legacy of use by children, sun weathered to the extent that its sky blue colouring has long since lost its lustre, remains dangling in suspension. Pointed directly downward, the undulating slide takes on new and more prophetic symbolism of a global economy in free-fall, plummeting to depths never before seen in our lifetimes, its plateau still as yet unknown. So too does the work now remind us of the public playgrounds closed the country over, as children, and indeed parents, experience the longest school holidays imaginable.

Lewis Fidock and Joshua Petherick, Tongue, 2019 was exhibited at Gertrude Contemporary from 30 March - 1 July. Courtesy of the artists.

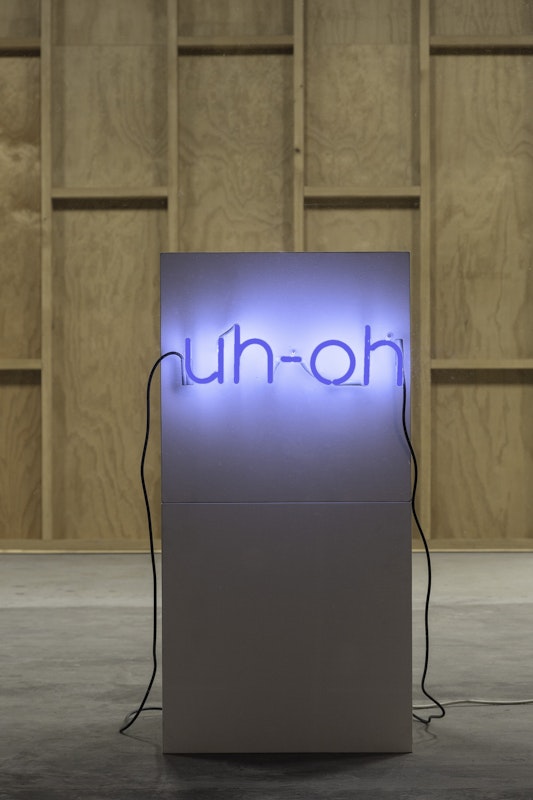

As the immensity of the situation barely began to become apparent, amidst a collective confusion wrought suddenly upon us, recent Gertrude Studio Artist Simon Zoric has installed his 2010 neon work Uh-oh prominently in the window, addressing the passing public with a directness and potent acknowledgement of the rapidly increasing gravity of the crisis. Flickering on and off, day through night, Uh-oh perfectly distils the realisation that we have little idea of what is going on, how long it will last, and how we might navigate a course out. With trepidatious humour, the utterance normally expressed under one’s breath, now projects as a beacon to the realisation that the situation is very much not under control.

Simon Zoric, Uh–Oh, 2010, Neon, 40 x 15 cm was exhibited at Gertrude Contemporary. Courtesy of the collection of Annemarie Kiely, Melbourne.

If Uh-oh suggests the realisation of a situation worse than previously thought, current Studio Artist Sarah Brasier’s work Everything IS a Bit Fucked, 2015 is the awakened awareness of a predicament more fully understood. Delivered with the immediacy and directness of a punk lyric, the statement offers apt summarisation of this moment, indeed, it could even be regarded as something of an understatement. Painted while Brasier was still in art school, and evoking a personal disenfranchisement, in the context we now collectively find ourselves within, the sentiment shifts from merely conveying the frustration of an individual to being a catchcry for the entire world.

Sarah Brasier, Everything IS a bit fucked, 2015, Acrylic on board, 40 x 50 cm was exhibited at Gertrude Contemporary from 30 March - 1 July and Gertrude Glasshouse 2 July - 3 November. Courtesy of the artist.

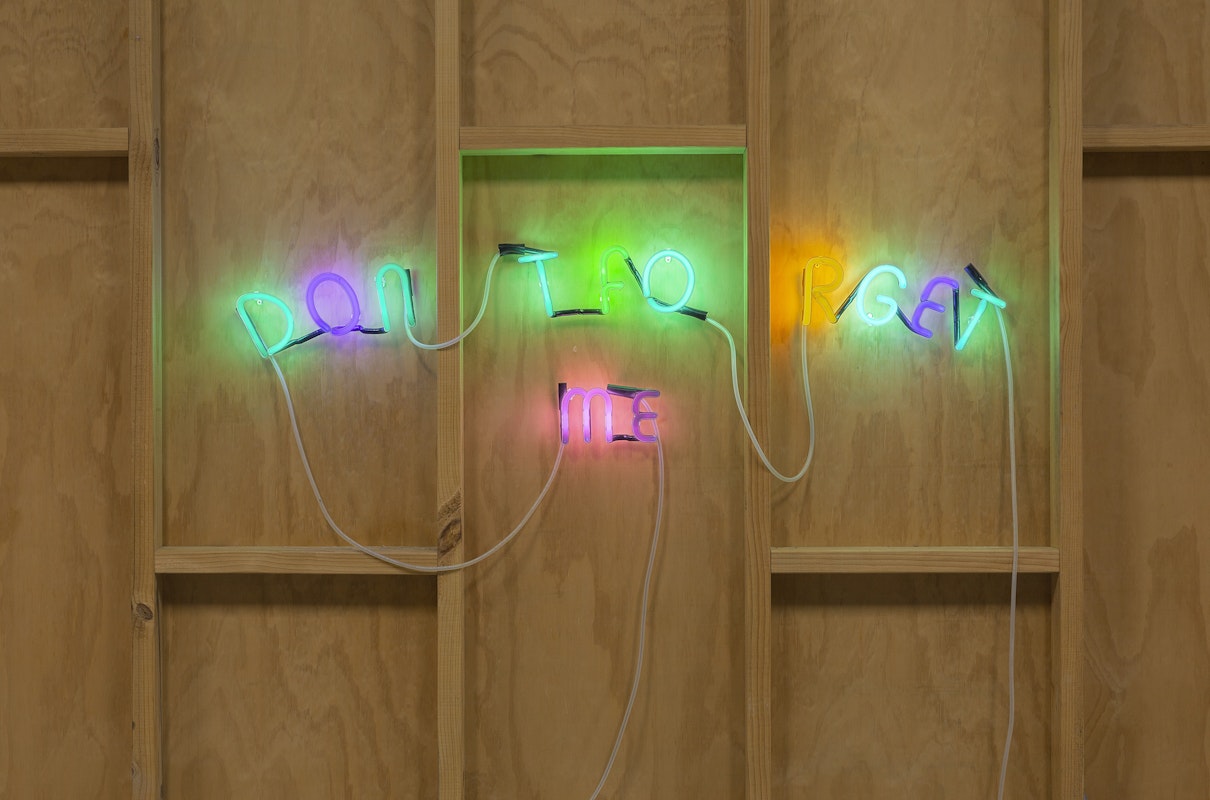

As the realisation of this situation sets in, we now find ourselves living in isolation, separated from almost everyone we know and love. Living a life of aloneness, hopefully as opposed to loneliness, we are nevertheless invariably dwelling upon questions of existentialism. With such solitude in mind, Studio Alumni Artist Kiron Robinson presents his neon work of 2008, Don’t Forget Me. Produced in a spectrum of colours, the words suggest a hope to not be dismissed or forgotten, asserting a presence even in a time of absence. In this context, the work speaks not just to the anxieties of the artist, but indeed to all of us.

Kiron Robinson, Don’t Forget Me, 2008, Neon, 70 x 120 cm was exhibited at Gertrude Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist and Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne

In the window vitrine of Gertrude’s Collingwood project space Gertrude Glasshouse, Grant Stevens’ presents his 2014 video work Just Dawn. The work draws upon a number of speeches by Gough Whitlam during his progressive, if short-lived, time as Prime Minister. As a leader committed to dramatic reformation and setting a course for a new direction in Australian society, Whitlam set a trajectory toward a more caring and just horizon. In the work, a series of words and phrases fade in and out of focus atop an abstracted and at times unsettling rendering of a horizon line of a computer-generated dawn. Accompanied by a muzak-styled soundtrack, the selected phrases and the disorienting horizon oscillate between the optimistic and unsteady, imbued now with a prophetic potency in this time of uncertainty and reliance upon decisive political leadership, we hope.

Grant Stevens, Just Dawn, 2014, HD video, 3 minutes 15 seconds was exhibited at Gertrude Glasshouse from 2 April - 1 July. Originally commissioned by Blacktown Arts Centre in 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Sullivan + Strumpf, Sydney and Singapore; and Starkwhite, Auckland.

In a different world, dancer, choreographer and artist Amrita Hepi would have opened her latest project at Gertrude Contemporary some weeks ago. With that project now postponed until early next year, a recent video work by Hepi, Dance Rites (2017), is reprised and recontextulised within the accumulating Hope in the Dark. The work looks at the body as the ultimate archive and vehicle of cultural identity, probing understandings of cultural authenticity through the lens of a dance floor or performative space. Somewhat eerily, in addition to the questions raised around the depiction of the black and brown female body, with its focus on a lone dancer performing within a theatre absent of viewers, the work reminds one of the lonesomeness of this seemingly never ending moment.

Amrita Hepi, Dance Rites, 2017, HD video, 7 minutes 19 seconds was exhibited at Gertrude Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist. Originally commissioned by Ace Open.

Darren Sylvester’s 2018 photographic work, ominously titled The End, was originally produced in reference to the end titles for films created by Universal Pictures. In the days of black and white films, the slogan used by the production company for the final frames was ‘The End. It’s a Universal Picture’. What would have then been a symbol of US efforts toward global cultural distribution now holds as a gloomy signifier of a pandemic’s expansion across the world. The fact that Sylvester’s staged reproduction of the filmic frame prominently brandishes The End in front of an image of earth focused upon the USA now further suggests a shifting of empire by a nation besieged most rampantly by this crisis.

Darren Sylvester, The End, 2018, 160 x 240 cm, Lightjet prints was exhibited at Gertrude Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist and Neon Parc, Melbourne: and Sullivan + Strumpf, Sydney and Singapore.

Well known for her text-oriented offerings reflecting the realms and intersections of labour and artistic practice, Rose Nolan has forged a visual language that creates an elaborating lineage between Russian Constructivism and present modes of social, cultural and political discourse and production. In her work, It’s hard to see what this all means (2019), a message of confusion that could readily be applied to many gallery or museum contexts, here directs us to apply the question with more weighty existentialism. In this time of certain uncertainty, the sentiment expressed through the work poetically signifies an inability to make sense of a world unraveling around us. The utterance is no longer one of individual doubt, but rather, a summation of a collective inability to comprehend a world and existence rendered so volatile and unpredictable.

Rose Nolan, It’s hard to see what this all means, 2019, acrylic paint on cardboard, 21.5 x 190 x 16 cm exhibited at Gertrude Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne.

Tina Havelock Stevens’ Ghost Class, 2015 highlights the aloneness of our current circumstances, our inability to witness live music, and the geographical estrangement caused by national and international travel restrictions (or for Melburnians under Stage 4 restrictions, even 5km beyond our homes). Through this, the work speaks to three different frames in time. In the immediate, we are experiencing life mostly in isolation; in the foreseeable future, the possibility of a congregating around live music remains suppressed; and the prospect of global travel even more distantly abstracted into the future. Performed and filmed in the Mojave Desert at a dystopian site used to accommodate deaccessioned aircraft, the work presents a sonic tribute to this environment of decay and abandonment. The raucousness of the drumscape now offers a degree of solace in a world starved of live performance.

Tina Havelock Stevens, Ghost Class, 2015, HD Video, 11 minutes was exhibited at Gertrude Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist.