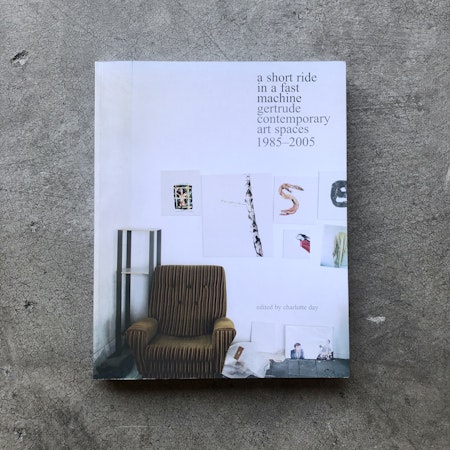

In this exhibition we begin with a period of time: from 1995 to 2005. Without trying to survey this decade, the curatorial framework references the practices of three artists associated with Gertrude’s exhibition and studio programs between 1995 and 2005, each of whom developed a rigorous and distinct conceptual approach to making art that hinged upon bringing together multiple points in time and/or space: Mutlu Çerkez, Damiano Bertoli, and Masato Takasaka. For a moment, we will put aside the incredibly rich context and the breadth of research of each artist’s practice, as nor does this exhibition attempt to survey the work of Çerkez, Bertoli, and Takasaka.

Instead, as curators, we asked eight artists to present one of their artworks from Gertrude’s history: either in conversation with another artwork from a different moment in their career, or to rethink the original artwork across a timespan of twenty or more years. The dominant critical exhibition mode of the period—installation—necessarily informed this approach, due to the ways in which installation art challenges modes of archiving and acquisition. Many of the works we were interested in exhibiting from this period no longer exist, or an authentic presentation of the original was not possible. As such, the artworks needed to be translated across different sets of conditions in space and time. This act of translation allows each of the artists to re-engage their own history of practice, re-presenting artworks along timelines that loop, multiply, and collapse.

The timeline of an artistic oeuvre became a concern for Çerkez not long after art school. He developed a conceptual framework in which he would co-date each artwork with a date in the future; a date at which he would theoretically remake the original. This framework challenged the linearity of an artistic career, or how art history narrates an individual practice through notions of progress, evolution, or even regression. It could be said to sit at odds with Gertrude’s legacy of supporting emerging artists because Çerkez’s future-dating system meant that he skipped the ‘emerging’ phase altogether.

Çerkez’s dating system implicitly asks what it means to remake an artwork again in the future. Rather than being perfect replicas, the few artworks that he did remake before his death in 2005 bore only oblique relationships to their originals. Of this fact, Francis Plagne notes, ‘Çerkez’s haphazard enactment of his date system shows us that the results of putting it into practice were less important than its effect of implying an overarching conceptual context that transcends each individual work and emphasises self-reference over any give-and-take with the outside world.’(1)

As Çerkez’s close friend Stephen Bram put it, ‘Mutlu was not a joiner.’(2) Sometimes he would encode acts of refusal as a form of participation. Rather than exhibiting at Store 5, he made the gallery’s sign. When Max Delany invited Çerkez to exhibit in the 1995 Gertrude exhibition Wall Drawings, instead of making site-specific wall paintings like other artists in the show, he exhibited a photocopied floorplan from his recent solo exhibition at Anna Schwartz Gallery—bringing the architecture of the slick Flinders Street site into the grungey Fitzroy building.(3)

The self-referential nature of Çerkez’s practice clearly influenced the younger artist Bertoli (Gertrude Studio Artist 1999-2001), for whom the year 1969 was an integral aspect of his studio research. This engagement with the year of his birth was an opportunity to frame, as Amelia Winata would note, a ‘nexus point between modernism and the contemporary and, therefore, an apt moment from which to pivot back and forth in time.’(4) The visual plane of the collage and the temporal plane of the montage were spaces that allowed Bertoli to replay histories, overlay histories, or make distinct histories simply touch. He named this method ‘continuous moment,’ bestowing his major solo exhibition at Gertrude Contemporary in 2003 with the same title. ‘Continuous Moment’ went on to become a naming convention for many future bodies of work, thereby suggesting, like Çerkez, a means of conceiving his practice in a holistic and systematic way.

Bertoli’s Continuous Moment (2003) was a reconstruction of the smashed iceberg depicted in Caspar David Friedrich’s Romantic painting Das Eismeer (1823–24), which Bertoli ‘extended, or continued’ into a three-dimensional sculpture that wrapped around Gertrude’s central column.(5) Despite going on to show this work at the National Gallery of Australia and Geelong Art Gallery, this significant work was never acquired by an institution and now endures solely as photographic documentation, sketches, and parallel works, like the two oil paintings of his minimalist iceberg from 2004. Its physical absence informs, in part, the structure of this exhibition.

Where Bertoli explores continuity through collage and montage, Takasaka embraces cyclical and looping forms of repetition and aggregation—all of which are inflected with a famously meta sensibility. Methods of appropriation and the readymade provide Takasaka with the opportunity to accumulate different timelines within a single artwork. Takasaka describes his perpetually generative system as ‘“the artist’s practice as always already-made.'(6) He continually creates new art from prior instances of his own practice or ‘back catalogue,’ in a manner, ‘akin to the “shuffle” function on an iPod’ or randomised Spotify algorithm.(7) Takasaka thinks of appropriation art through the musical prisms of the cover version or the ‘session muso,’ drawing, in a recent essay, parallels with Çerkez’s abiding interest in the musical form of the bootleg recording.(8)

In addition to music, architecture—both paper and actual—has exerted an important influence on Takasaka’s work. Having studied architecture, Takasaka has gone on to make foamcore models of the gallery spaces in which he is to exhibit as a form of preparation—sometimes then folding the architectural model into the final installation itself, as he did for his 2012 solo exhibition at Gertrude Contemporary, Almost everything all at once, twice, three times (in four parts…). True to form, Takasaka continues this practice in his ALMOST ALMOST EVERYTHING ALL AT ONCE, TWICE, THREE TIMES (IN FOUR PARTS...) RETURNAL RETURN REDUX*works from the permanent collection and selected loans from the EVERYTHING ALWAYS ALREADY-MADE STUDIO MASATOTECTURES MUSEUM OF FOUND REFRACTIONS (1977-2025) for 1964, 1969, 1977, 1995, 2005, 2025. Here, he creates an architectural model of the architectural model of the old Gertrude in the new Gertrude, which becomes the basis for a sprawling installation that reflects on the artist’s own exhibition history at Gertrude.(9)

Takasaka’s work is purposefully installed in the education room that holds the recent memory of the preceding exhibition, where Gertrude’s 1985–95 archive was displayed. Here, his work is intended to reflect key aspects of the overall exhibition’s organising logic: archival reconstructions, recursive self-reflection, architectural displacements, and temporal collapse.

The curatorial framework for this show also builds on an earlier curatorial collaboration at 200 Gertrude Street made to commemorate the 40th anniversary of another Fitzroy institution: 3CR Community Radio station. For this 2016 exhibition, we wanted to think about Gertrude and 3CR together in relation to collective action and progressive politics. In particular, we were interested in bringing together the two institutions to see how they have respectively dealt with the gentrification of the Fitzroy-Collingwood area over their multi-decadal histories. 3CR notably collectivised to buy its building on Smith Street in 1984 (as one of the programmers remarked to us at the time, ‘communists make the best capitalists’”), whereas Gertrude was ultimately priced out of its rental property in 2017. For 1964, 1969, 1977, 1995, 2005, 2025, Panigirakis has built a to scale replica of the ground floor of 200 Gertrude Street on its original axis, such that it diagonally bisects the Preston South site. This exhibition design weaves itself in and out of the existing galleries, with the old space haunting the new. Restaging the spatial parameters of 200 Gertrude Street in Preston South speaks to the difficulty in restaging artworks that were originally site-specific and references a site now occupied by a high-end fashion outlet, keeping the issue of gentrification front of mind.

Clinton Naina (Meriam Mir, Torres Strait/ KuKu, Cape York) has reconstructed an installation from the front gallery of Gertrude from 2000. Titled Heritage Colours, it addresses the distinct but interrelated histories of colonisation and gentrification of Melbourne’s inner north, as well as the Country beneath its paved streets. The original exhibition featured a thick layer of mud on the floor with a scattering of discarded objects—such as a plastic chair, a car door, and glass bottles, all covered in layers of paint. A digital print of an iron fence was adhered to the front window of the Victorian building, creating a new boundary and sense of private property. On the gallery walls were a series of monochrome prints that indexed colonial colourways designed to maintain the appearance of heritage listed buildings, many of which can be found around Gertrude Street. The commercial paint names of these colours betray colonial histories of extraction and dispossession: Parramatta Red, Brunswick Green, Colonial Cream, Mission Brown. As the exhibition’s original curator Samantha Comte remarked in her catalogue essay, the act of repainting buildings in these colourways points to the ongoing, day-to-day maintenance of colonial infrastructures, and the question of whose cultural heritage is preserved.(10)

In reconstructing Heritage Colours twenty-five years later, Naina has added several new elements to the installation: a tall, suburban back-yard fence that both encloses the scene and blocks optical access from most vantage points in the gallery; and a projection of a series of photos of Fitzroy streets from the early to mid 1990s, when Naina began the research for Heritage Colours. Amongst the projected photographs in the 2025 reconstruction is one of the vacated Victorian Aboriginal Health Service when it resided on Gertrude Street. The building’s exterior is painted up boldly in the colours of the Aboriginal flag, gesturing towards—as Naina put it—a different set of heritage colours, as well as to the range of neighbouring First Nations-led organisations that have made Fitzroy a site of enduring significance for Victorian Aboriginal communities.

In 2002, Raquel Ormella presented a solo exhibition Living in Other People’s Houses in the main gallery at 200 Gertrude Street that, like Naina’s Heritage Colours, spoke back to histories of gentrification, dispossession, eviction, and private property—themes that are crucially important to the history of Gertrude Contemporary and its own eventual relocation from Fitzroy to Preston South. At the time, Ormella’s life and practice were shaped by her activism around squatting, housing-cooperatives, gentrification, and living as an undocumented unhoused person. Building on earlier projects like Rental beige (incomplete) (2000) and I used to live here (2001), the materials of Living in Other People’s Houses were of the everyday and reference DIY forms of agitprop. Works included: a textile banner appliqued with the words ‘this would be easier if I was making a documentary’; a cardboard protest sign inscribed with the phrase ‘this is not the life my mother wanted for me’; a series of soft sculptures spelling out the word ‘stay’ made from cheap, plastic moving bags; and a table sporting an assortment of printed materials that documented the traces of several graffiti interventions by the squatters at the Gunnery, and one—‘Brief Utopia’ made by Lucas Ihlein, Mick Hender and Ormella—that had several iterations on buildings occupied by the artist-run initiatives the Verge in Perth and Squatspace, which was set up in a vacant building on Broadway, Sydney in 2000. Curator Wayne Tunnicliffe reflected: ‘While her works rehearse the classic issues of left-wing politics—ownership and economics—Ormella inflects them with her own anxieties about making and exhibiting artworks—production, distribution and reception—and the vexed issue of political efficacy in art practice.’

In addition to Living in Other People’s Houses, Ormella presents a new and related body of work titled A page from an incidental biography (2024–25). It is a series of drawings on recycled envelopes from various superannuation companies, employers and cultural organisations, a material trace of the way we continue to live in and move between other people’s houses, as well as to the way precarious labour leads to the accrual of numerous superannuation funds. The drawings reflect the artist’s movement between rental properties and lovers’ homes, over a twenty-five year period with the most recent address, the house that the artist has bought in Canberra. Some of the text on the drawings refers back to earlier works, such as Rental beige and I used to live here, whilst the choice of material reflects Ormella’s ongoing commitment to leaving a light ecological footprint in her practice.

In 2002, Lane Cormick (then a Gertrude Studio Artist, 2001–02) presented Vanilla Sigartje in Studio 12. It was a video work documenting a performance in which Cormick can be seen learning to speak Dutch in conversation with the artist Irene Hanenbergh. They speak in a series of disjointed phrases, such as:

Good shave/mooi glad gerschoen

Very close/erg glades

Very close/erg glad

Nice shirt/een nieuwe blouse

Tailor made/op maat gemaakt/kleermaker/passend

Very comfortable/het zit erg lekker en comfortabel

This exchange takes place against a sleazy backdrop: an unmade bed that sits atop cowhide, an open bottle of Cognac, their jackets hanging side by side on hooks, while a Joy Division record murmurs in the background. What looks like a cheap hotel room is in fact a stage set that Cormick built in his Gertrude studio, and which is documented in a photograph of the artist taken by Cath Martin at the time. In the video documentation of Vanilla Sigartje (2002), Cormick was interested in capturing a Godardian-type reveal of this set—to evidence its artifice, rather than paper over its illusion. In so doing, he creates a mise en abyme of production and presentation, a dynamic that has always characterised Gertrude as an institution, as curator Tara McDowell observed in her 2014 exhibition, Octopus 14: Nothing Beside Remains.

Vanilla Sigartje was one of a number of performance works that Cormick staged during this period. For the 2025 remake, Cormick has recreated the set as an open-ended stage with the original painting and one of Hanenbergh’s jackets, rather than restaging the performance itself. The artist’s gesture of bringing a bed, alcohol, and music into the gallery conjures the sociality of 200 Gertrude Street and the various surrogate or para-artistic uses of its studios.

Katherine Huang was a Gertrude Studio Artist in 2005–06. Before then, in 1999, she exhibited a work titled The Stave Tree’s Produce in the group exhibition Same as it ever was, curated by Clare Firth-Smith. Huang’s 1999 work played out a studio method that she used in a number of exhibitions in the period. A site-responsive arrangement of many things: some crafted, drawn, and constructed; others found, catalogued, and organised from the course of Huang’s daily life—oftentimes picked up on the way to or from the studio. This careful orchestration was not the random scatter of art history, but a series of rhizomatic associations, a horizontal distribution of objects that, on a macro level, appear somewhere between an architectonic model and an abstract assemblage. These associations are, as curator Bridget Crone noted, ‘a delicate process, and one in which the artist is involved in the complex operation of making and remaking the work, articulating a passage here, removing something there.’(11)

Any process-based work like Huang’s is not just an experiment in form and material, but a record of decisions made across time. Accordingly, the 2025 iteration amalgamates timelines both short and long. To begin, Huang used a thorough list that she drafted twenty-six years ago to document the original work. But for the 2025 translation, adherence to any sense of an original is not important. This process resonated with Bertoli’s studio logic, who reflected on Huang’s work in a 2001 LIKE Magazine article, where he described it as ‘an accumulation of explored tangents and endless detours’ and ‘a multi-directional flow of alternating velocities that never reaches a conclusion, and lead[ing] only to further possibilities and propositions.’(12)

In July 2004 there were 413,599 members on RSVP, then one of Australia’s largest dating websites. One month later, the membership had grown by 17,000. The exponential growth of dating websites and apps since then means that a quarter of all Australians under the age of forty-four have met their partner online and half of the same demographic are actively using apps. Whilst using these sites and apps was not unusual in 2004, it would be fair to say that they had not yet entered the mainstream. For Vox Virtua, Linda Erceg’s 2004 exhibition in Studio 12 (she was a studio artist 2003–04), the artist joined RSVP, activated a profile, and started dating. Her exhibition consisted of a desktop computer that was connected to rsvp.com.au, allowing the audience to search the website. In 2004, perhaps a simpler time for online relationship building, there was an option on the website for members’ profiles to be accessible to all, to members only, and non-members alike. This broad accessibility caused consternation amongst some in the (heteronormative) community at the time. It was felt that some (paranoid) ethical line had been drawn. Perhaps one didn’t openly admit to seeking dates, mates, and roots online. Revealing one’s profile at the time might be something done in the privacy of one’s home—not in a public gallery—regardless of the online open access.

In the same year as Vox Virtua, Erceg exhibited Urban Legends at CLUBS Project Inc, an artist run initiative across the road from Gertrude. Here, Erceg presented found correspondence, letters between one woman and a series of suiters: Peter, Jon, Rod, Dave, Ken, and Peter. For some of the men, there was only one letter; for others, a series that included some intimate photographs. Of course, we never needed the internet to find a hookup outside of real-life social and community settings. Since the early twentieth century, classifieds in various printed publications (mainstream to niche) have connected singles. Unlike the online versions of instantaneous messaging, responding to classifieds via mail meant your writing had to be more than—’hey, what are you into?’ Incidentally, this idea is also borne out by Çerkez’s 2004 series Various Responses, in which he made text paintings on paper that transcribed voice recordings left by potential matches through a telephone dating agency.

In Erceg’s more recent work, the artist joins a lineage of feminist practices (including, perhaps most famously, Mona Hatoum) that explore the materiality, abjection, sexuality, and gendered associations of hair. Hair Work (2025) is made from felted human hair collected from a hair salon. Instead of the photographic and textual descriptions of people's bodies, tastes, hobbies and vulnerabilities found in dating profiles, Erceg presents anonymous and abstracted representations of the human subject. In Hair Work’s materiality, multiplied and swarming, we are asked to understand the human body as a complex containment of once-discarded hair now resonating with curious keepsakes.

In 1995, Eliza Hutchison presented The Still Life and the Cleaner at 200 Gertrude Street. The installation consisted of a series of clues, objects laid out on an office desk, an arranged still life or, more aptly, a controlled presentation of evidence, signifiers for a missing or absent woman. The still life here conjures spectres of death, making this clinical arrangement a forensic one. Cleaning materials, cosmetics, and clothing, all leaning towards white, together construct the fictitious identity of Porphyria Blank. Informed by the poem, Porphyria’s Lover (1836), written by the Victorian poet Robert Browning, the tableau set up by Hutchison’s installation erases Poryphyria, resonating with the sexual violence of the original poem. Overlooking this object arrangement is a screen-based work: surveillance footage scanning the passageways and elevators of a hotel, Poryphyria offering her services in cleaning or in prostitution, her identity hovering on the brink of the domestic and public. In both cases, the woman is objectified—literally in relation to the still life, and through the psychic dimensions of being captured by the lens. The installation was built on Hutchison’s honours research from the previous year. Her exegesis, a fictocritical engagement in the first person, grapples with the complexity of identity formation and object relations through psychoanalytic feminist critique. Hutchison’s writing is not an explanation of any one artwork. It does, however, lay out a treatise, a critical reflection on the gendered underpinning of looking and being looked at both in domestic space and on a material level—how desire is sublimated in fetish, garments, and fashion more generally. In 2025, Hutchison uses artificial intelligence to animate a 1995 photograph of herself eerily mouthing fragments of this exegesis. Like a floor talk for an exhibition long gone, the artist reasserts the cultural politics of art practices like Hutchison’s own that are currently challenged by populist attacks on pluralism and identity.

In You might be anything. And I love you. (2025), instead of the objects associated with the fiction of Porphyria Blank, Hutchison documents the objects of her everyday domestic life through a series of 3D scans. The new work’s title uses a line borrowed from poet Gertrude Stein addressed to her partner Alice B. Toklas. Bras, toilet roll, false eyelashes, hair accessories, and floss-picks, flotsam found on the bathroom floor, become enigmatic still lifes that are underpinned by adornment rather than the fetishistic violence of the 1995 work. The 3D scanning of the detritus of Hutchison’s family life becomes something else—disassociated from its rudimentary function. The digital scanning transforms the grid of bathroom tiling into a virtual plane where scale and detail become abstract and ambiguous—small objects of a still life become glitched representations, uncanny and at times monstrous spaces of projection, that, as the title suggests, might be anything.

Peta Clancy (Yorta Yorta) was a Gertrude Studio Artist from 1995 to 1997 and, in 2000, curated with Alison Weaver the exhibition Remember Who You Are across the front and main galleries of 200 Gertrude Street. This was an exhibition that, in the curators’ words, encouraged ‘the viewer to pause and examine seemingly insignificant moments’ and ‘to slow time in a society that allows us less and less time to reflect, contemplate and look closely.’(13) It featured a range of works that focused on quiet objects, environments, and events that might otherwise be ignored or backgrounded, such as: bathroom tiles, domestic doors, and brick walls (Mark Wingrave); details of an abandoned house (Kenneth Pleban); a road crew filling winding, linear cracks in a bitumen path (Alison Weaver); and suburban walls and fences (Ken Arnold). Clancy presented three photographs that documented the process of cleaning a shelf in her home that had accumulated a thick layer of dust over time.

For the 2025 exhibition, Clancy is represented by two bodies of work—both of which bear testament to her commitment to slow and patient studio methodologies. She has recaptured a shelf replete with a new layer of ten years’ worth of dust. On the back of this wall is a more recent body of work, titled here merri merri lies (2024)—originally exhibited at Counihan Gallery as part of Kimba Thomson’s curated exhibition Future River: When the Past Flows. Clancy works, in her words, ‘on and with Country’—developing non-extractive modes of collaboration with Country. For here merri merri lies, Clancy sought permission from Wurundjeri Elders, Aunty Julieanne and Aunty Gail, from the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation, to photograph merri merri at Coburg Lake Reserve, which was artificially created in 1915. This is a site that is both close to Gertrude Contemporary and the house where Clancy has lived for twenty-five years. Clancy’s method is to return back to the site to show her photographs to Country created from her perspective and ask permissions from Country. Then, using a frame to suspend the photograph, she cuts away the lower or upper half of the original photograph and rephotographs the site—allowing multiple timelines to converge in the one, indexical photographic image. As the artist puts it, these images ‘explore Country from multiple time frames, perspectives, histories, as well as acknowledge the cultural memory still here.’(14)

Clancy’s photographs of the merri merri are installed on top of an even older image: an historical photograph of Coburg Lake and bridge from circa 1914-16, which she has turned into wallpaper, thereby producing an even more complex temporal layering. As the artist notes, ‘rocks in the creek bed were used to build a wall (near Newlands Bridge) forcing the creek water to back up and form the lake. This changed the trajectory of the creek and in turn flooded thousands of years of culture, history, and memory.’(15) Bluestones collected from the area are installed in the pattern of a creek on the floor, emulating the flow of water. The configuration of the bluestone may also suggest the demise and inevitable collapse of the bridge; the colonial structure submerged underwater.

At the centre of our decade is the year 2000. In the preceding years, the ‘Y2K’ or ‘millennium bug’ scare emerged as a result of a prediction that, when ’99 ticked over into ’00, computer calendar systems (which primarily relied on the last two digits for dating years) would not be able to distinguish between the year 2000 and 1900, leading to all kinds of computational collapse and hundreds of millions of dollars in damage. An artist exploring commodities and cultures in and out of time (and fashion), Lyndal Walker (Gertrude Studio Artist 2004–05) presented a series of photographs in an exhibition titled The Latest (1995), one of which depicted a billboard of a Windows 95 advertisement, highlighting the inbuilt obsolescence of technologies.

Cultural anxieties around the experience of time as ‘sped up’ by computer networks dates back to the 1960s with the advance of cybernetics. Art historian Pamela Lee coined the term ‘chronophobia’ to describe this widely felt anxiety and the art that meaningfully reflected it—by artists like Bridget Riley, Carolee Schneeman, On Kawara, Hans Haacke, and Robert Smithson. Dial-up internet became commonplace in Australia in the mid-1990s, and broadband by the early 2000s (as reflected in Erceg’s online dating artwork, Vox Virtua)—virtually collapsing points in time and space in ways that were both exhilarating and overwhelming. Clancy and Weaver’s desire, in 2000, to make an exhibition that slowed time ‘in a society that allows us less and less time’ is in this respect revealing, as is Bertoli’s carefully calibrated decision to return to the long 1960s in order to critically examine historiographic and temporal models from the vantagepoint of the present. Thinking with artists’ methods, 1964, 1969, 1977, 1995, 2005, 2025 offers a structural framework for contemplating this time.

1. Francis Plagne, ‘Mutlu Çerkez: variations on nothing’ in Mutlu Çerkez 1988-2065, Monash University Museum of Art, 2018, p. 18.

2. Stephen Bram, conversation with Helen Hughes and Masato Takasaka, February 2025.

3. Between 1995 and 2005, Çerkez also contributed to several other Gertrude programs, including: Bram’s curated exhibition Practice as Technology in 1996; the Hot Rod Tea Room exhibition (based on the magazine issue Hot Rod (Issue no. 12), in which he was interviewed by Damiano Berotli) in 2001; and the collaborative wall painting AND with Marco Fusinato in 2003, which was recreated in 2017 for the final exhibition at the 200 Gertrude Street site, The Beginning of Time. The End of Time.

4. Amelia Winata, ‘Damiano Bertoli 1969 - 2022,’ Memo, 13 October 2021, https://www.memoreview.net/reviews/damiano-bertoli-1969-2021.

5. Damiano Bertoli interviewed by Mark Feary, October 2017, https://gertrude.org.au/article/damiano-bertoli-artist-interview.

6. Masato Takasaka, Appropriating appropriation: the artist's practice as always already-made, Monash University, Ph.D thesis, 2019.

7. Masato Takasaka, ‘The Artist’s Practice as Always Already-made: Remaking and Repetition in the Work of Marcel Duchamp, Mutlu Çerkez and Masato Takasaka,’ The Art of Laziness: Contemporary Art and Post-work Politics (Melbourne: Art & Australia Publishing, 2020), p. 159. Masato Takasaka, email to the authors, March 25, 2025.

8. Ibid.

9. Takasaka was a studio artist in 2001-2003; held the aforementioned solo exhibition in 2012; and exhibited in the experimental group exhibition Inverted Topology in 2005.

10. Samantha Comte, Heritage Colours, exh. cat. (Melbourne: Gertrude Contemporary, 2000), n.p.

11. Bridget Crone, Concrete Living Room, exh. cat. (Melbourne: 1st Floor Artists and Writers Space, 2000), p.3.

12. Damiano Bertoli, ‘Baby Mess: The Work of Katherine Huang,’ LIKE Magazine 16 (Spring 2001).

13. Peter Clancy and Alison Weaver, Remember Who You Are, exh. cat. (Melbourne: Gertrude Contemporary Art Spaces, 2000), n.p.

14. Ibid.

15. Peta Clancy, artist statement, Peta Clancy, https://peta-clancy.squarespace.com/new-page-64.