Mark Feary: What is the significance of the title HEADLESS?

Rob McLeish: I’m used to titling shows in response to a specific new body of work, so this time was quite different in that the work in the show spans about 15 years and I needed something that would bring all of that together. I played around with lots of different titles for the show until one felt right. And HEADLESS felt right straight away. All I’m really looking for in a title is a vibe. If I think about that title there’s references to various things like Acéphale, Georges Bataille’s publication from the 1930s and his general writings about headlessness; Douglas Harding’s text on meditation, On Having No Head: Zen and the Rediscovery of the Obvious; as well as decentralised systems where there’s no hierarchical control. But mainly for me I think I was drawn to how specific the title is whilst simultaneously being very am- biguous. The latent violence of it is also very poetic in terms of getting beyond the illusion of self, it’s hard to put your finger on and I like that.

MF: This show brings together a selection of works spanning back almost 15 years? What was your process in selecting the works you did, and what kinds of dialogues were you thinking in relating these works to one another and in connection with the new works.

RM: It was an interesting process because at times it’s felt like my work has been all over the place but looking at this selection it’s surprisingly coherent. The guiding parameter that I set was to exclusively focus on sculpture, that helped a lot. It’s all sculpture except one obscure video work, but even with that work it’s essentially a video of a sculpture. Once I decided it was going to be a sculpture show, I selected works that were personal favourites and ones that worked well

in conversation with each other. It’s always a visual conversation between works and the connections through materials, techniques and content become pretty apparent, pretty quickly. It’s like putting together a playlist. Most of the new works in the show introduce a significant shift in scale and some crucial colour that plays a subtle but important role in punctuating the overall palette which is otherwise very restricted, muted and über cold. For me the hot water bottles bring a different kind of bodily presence into the conversation, literally and metaphorically.

MF: For the River Capital Commission, you have made two new series of works. Both series have a domestic orientation to them, the hot water bottles and the cast beach combings? What are the underpinnings of these reference points, which, in contrast to some of the austerity of other projects, register as quite comforting, even homely?

RM: A lot of the existing work that I’d selected for the show is large in scale and quite harsh and intense. I wanted to introduce some new work that was smaller in scale, mellower, and perhaps a bit more subtle or at least just a different kind of poetic. I saw it as an opportunity to expand my visual language a bit, it didn’t seem to make much sense to produce two or even three new works of the same (large) scale that were more or less the same as previous works. So I shifted it and you’re right, it is a lot more domestic. And it’s a weird environment to introduce that kind of domesticity into because it’s very sterile, synthetic and stylised.

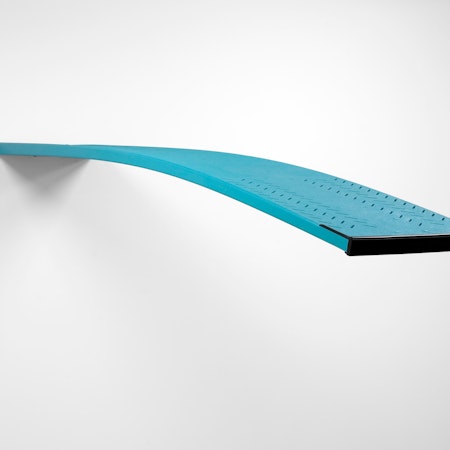

As soon as I started playing around with the ‘hotties’ I realised they’d play a similar role to Ugo Rondinone’s sleeping clowns, they’re like a footnote to that. With the beach combings, I enjoy playing around with hi/low brow aesthetics/culture. The original objects themselves are very interesting the way they form. They’re fossilised tubes of sand which are the remnants of decomposed root systems, they’re like moulds for absent arteries. I wanted to fuse that with the aesthetics of fake aquarium coral and subtle references to BDSM.

MF: The series of these new works Bound Composition (2021) are the first works I have seen by you that reference organic matter, rather than overtly industrially produced structures, sporting equipment, and the like. You’ve had a sea change, wisely, ahead of all of the lockdowns, moving to the Mornington Peninsula. Are these works in some way inspired by the new setting of your studio and living scenario?

RM: Yes in a pragmatic way they are because I spend a lot of time at the beach and those forms are found there. I think the biggest influence in deciding to use them was where I was at creatively after coming off the Neon Parc show earlier this year (Distortions, Neon Parc, Melbourne, 2021). That show was so dense in terms of subject matter, it was a pretty intense body of work, a lot of it was loud, confrontational and jarring. I was genuinely worn out from making all those drawings.

I wanted to produce a series in a lower key manner, but still keep it well within my oeuvre and I’d see those sand tubes every day. A wanted it to be relatively gentle and very simple in terms of just combining two found forms to create a new form. Simple, direct and poetic, but still synthetic. I was also drawn to these forms as being a marker of time.

MF: As a precision-oriented fabricator, where does failure sit in relation to process, with many of your works devised, carefully thought through and technically resolved? Is there tolerance for happy accidents? Does this play out more in the drawing and screen-printing aspects of your practice, rather than in the sculptural sphere?

RM: There’s definitely a spectrum, with some of the sculptures being completely planned out with no room for error, and some being right at the other end where it’s all about spontaneity, chance, gesture and driven by happy accidents. Examples of that looser approach are the works that incorporate the epoxy clay. As a material you only get between 2-3 hours where it’s malleable like water-based clay before that process is truncated by the epoxy curing into a solid, rigid state. So, you have to work very quickly, it can’t be too planned out. I often bring the two ends of that spectrum into a single work. It’s much more fun to embrace all the accidents and I love working like that, but I also want to combine that with a certain kind of precision. And you just have to do the work to achieve that, it’s a grind. The precise work is relentless and it’s tiring to produce. Drawing is definitely a release, because it doesn’t have any of the burdens of physics.

It lends itself to being preliminary and experimental, if it doesn’t work out it’s no big deal. It’s where I can work quickly and it’s very liberating for me, even though some of the drawings are also pretty relentless.

MF: On the topic of relentlessness, your Neon Parc solo exhibition from earlier this year, Distortions, presented over 60 pencil drawings, all executed in the same colour, all of the same dimensions, produced over the course of the lockdowns. Was this a responsive form of catharsis, or something that you had been thinking about for while?

RM: I’d been thinking about it for quite a while but the lockdowns provided all this extra time to really expand the project. There’s an obsessiveness to those drawings that probably thrives in isolation.

MF: Conceptually, the idea of contortion and physical degradation permeate your works. Often with regard to athleticism and aspects of sport. It is this a kind of unpacking of perfection, of classical sculpture depicting victory, to present a kind of monumentalisation to not winning?

RM: For me it’s normally in relationship to formalism in an art historical context. Notions of formal correctness. That’s why gymnastics is a good motif for me in a way that football wouldn’t be. Yeah, I think it could be seen as an unpacking of perfection, as highlighting the severity and the impermanence of it.

MF: Who is your audience, who are you trying to speak to?

RM: I don’t have a specific audience in mind. Predominantly I just have to keep it interesting and engaging enough for myself, that’s where the drive comes from, the compulsion to want to make the work. Part of that is being engaged in an ongoing dialogue about art and placing my work in that context. But it’s always going to read differently depending on differing audience perspectives. At the end of the day, it’s a visual language, it’s aesthetics and it’s for anyone who cares to look.

MF: Given the opportunity and resources, what is a project that you would like to someday make?

RM: Dusting off the old mechanical bull video for this show reminded me of a work that I’ve wanted to make for years. It would be another mechanical bull video, very similar, fixed shot, but this time the bull would be placed into an empty bath and left to buck itself to the point of disintegration, destroying the bath in the process.